On Boxing Day 1962, when Juliet Nicolson was eight years old, the snow began to fall. It did not stop for ten weeks.

The threat of nuclear war had reached its terrifying height with the recent Cuban Missile Crisis, unemployment was on the rise, and yet, underneath the frozen surface, new life was beginning to stir.

From poets to pop stars, shopkeepers to schoolchildren, and her own family’s experiences, Juliet Nicolson traces the hardship of that frozen winter and the emancipation that followed. That spring, new life was unleashed, along with freedoms we take for granted today

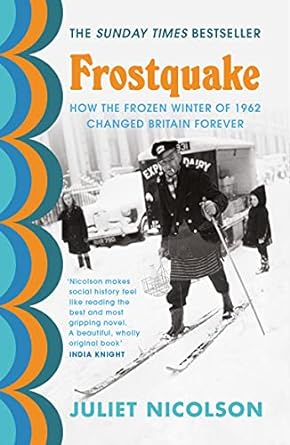

Our read for our November meeting was Frostquake by Juliet Nicolson. Although this book had looked interesting, with its cover picture of a milkman on skis, it did not exactly live up to expectations. When we got together to review it, we found that only two of the group had read the whole book, and several had either given up completely, or hadn’t had time to read it (but were planning to). This didn’t stop our discussion, in much the same way that the snow didn’t stop life in 1962!

Several of the group said that the book wasn’t what they had been expecting. Rather than a memoir about how the snow had affected daily life for the British people, it seemed to be occasional facts about the weather, memories of Juliet Nicolson, and the political and social history of the 1960s. The title ‘Frostquake’ seemed to be being used as an analogy with a frozen period leading to great change, however this wasn’t felt to be strictly accurate as the weather was a coincidence, rather than a trigger or cause for the changes. It was commented that the author seemed to have found a niche as her previous book was about the British heatwave in 1911.

The book felt well researched – the biography lists diaries, letters, and books that the author had studied, as well as conversations she had had with people involved. Excerpts and anecdotes in the text included Joanna Lumley’s school days, John F Kennedy, Juliet’s memories of life at Sissinghurst with her family, the early years of the Beatles, the creation of TV satire, Sylvia Plath’s death, and the Profumo affair. It also included a (very) few assorted descriptions of life in the big freeze, such as a model getting lost in the snow and accidentally driving on to the parade ground at Buckingham Palace, feral New Forest ponies, milk shortages because the milk lorries couldn’t reach the farms, the ever present strikes and work to rule, and the Trafalgar Square fountains being turned off. Several of the pages had comments and mentions of events that made our members look for more information to put into them context. Lots of the politics mentioned, especially references to America such as John F Kennedy’s affairs with members of the typing pool, didn’t seem particularly relevant to the bad weather or Britain in the deep freeze.

Frostquake seemed to be a book for those who wanted to reminisce. It felt as though it were aimed more at people who were around in that era who may not have been aware of the big news articles due to age or location. The event order felt jumbled, even though it was a social history rather than a narrative. In fact it felt as though the Beatles were a more important part of the book than the weather itself – they had almost a whole column to themselves in the reference pages.

On finishing the book, one reader said it almost seemed like the author had been trying to create a single picture from several different jigsaws with missing pieces. Juliet Nicolson definitely created an interesting picture, but it wasn’t necessarily what our readers had been expecting or hoping for.

Our read for our December meeting is The Ecliptic by Benjamin Wood.

On a forested island, off the coast of Istanbul, stands Portmantle, a gated refuge for beleaguered artists. There, a curious assembly of painters, architects, writers and musicians strive to restore their faded talents. One, Elspeth ‘Knell’ Conroy, is a celebrated painter who has lost faith in her ability and fled the dizzying art scene of 1960s London. On the island, she spends her nights locked in her blacked-out studio, testing a strange new pigment for her elusive masterpiece. But when a disaffected teenager named Fullerton arrives at the refuge, he disrupts its established routines. He is plagued by a recurring nightmare that steers him into danger, and Knell is left to pick apart the chilling mystery.

Described as: ‘An intelligent examination of creativity, psychology, and a riveting mystery. . . this ambitious novel will haunt the imagination long after the final page’ (Independent on Sunday)

A wonderfully written, beautifully detailed, hallucinogenic novel. . . Rich, strange and clever’ (Sunday Express)

‘A resounding achievement. One of the most absorbing explorations of the artistic process I’ve ever read in fiction. . . Wood’s action writing is superbly purposeful and unself-conscious. . . Rich, beautiful and written by an author of great depth and resource who is clearly giving his all in the service of that most taxing of endeavours: the writing of a fine novel’ (Guardian)

We will be making our own minds up on 20th December at 1pm. Pop into the Education Centre Library to borrow your copy and request your Teams invitation.