The joint book group choice for this month was Lioness by Emily Perkins. Described as ‘perfection’ (Glamour magazine), ‘a thoughtful, intelligent novel about one woman’s search for more meaning’ (Good Housekeeping), ‘a coolly ironic look at modern womanhood’ (The Times) and ‘a well-told story of family rivalry and sibling whining’ (Independent), we couldn’t wait to add our own opinions to the throng of reviews.

To say that we loved this book would be a (slight) lie. Lioness was described as ‘Marmite’ by one of the group – but this may be unfair to savoury yeast extract (other brands are available). Another reader described it as ‘meh’, and yet another said ‘it wasn’t my cup of tea’. Several readers abandoned the book only a few pages in. Those who made it all the way generally found it irritating and predictable (although one person said it was compelling – a view not wholeheartedly shared by the group!)

So what about the plot? The story opens by introducing us to Therese (formerly Teresa) who owns a luxury homeware and lifestyle company. She has been married to Trevor, a property developer 20 years older than her, for 30 years, and is stepmother to his four (over indulged) children. Therese has everything – and has been moulded by Trevor into being the perfect wife. On the cusp of his retirement, Trevor’s business dealings come under scrutiny, and the edifice of their privileged lifestyle begins to show some very unstable foundations. This causes Therese to examine her life, her choices and her place in a family that has never fully accepted her.

The themes of privilege, affluence, self-discovery, ageing, and female rage set in a cast of, it has to be said, fairly unlikeable characters make it sound like a worthy and interesting read. However aspects of the story, such as Therese’s friendship with the unconventional neighbour Claire (presumably intended as a catalyst for Therese’s self-examination), don’t quite ring true. Claire’s unconventionality seems to be trying a bit too hard and ventures into the realms of caricature. Other characters are stereotypical, i.e. the stepchildren (universally loathed by our readers) or the character of Trevor himself (generally viewed through Therese’s noncritical gaze).

The quote from the backcover of the book calls it “a hypnotic portrait of women unravelling and being unravelled…” which did seem to fit the story quite well. However it also led to some readers questioning whether it could be autobiographical. When the group pondered what the point of the story was, it was hard to come up with an answer.

While it was interesting reading a book based in New Zealand, it was easy to envisage the same storyline against a UK or US background. The internal struggles of Therese, and the rushed ending meant that the novel wasn’t as engaging or thought provoking as it perhaps wanted to be. Therese’s journey of self-discovery takes place over a long portion of the book but whether she actually managed to find herself or what she was looking for seemed muddled, although we did get closure for both the financial irregularities looming over the story, and for Claire’s backstory.

The plot feels over dramatized in places, although some readers liked the way that tension built through the novel. It always felt like it was on the cusp of something big happening – but then nothing really did. In summary, Lioness appears to be a novel about the visibility of women, the power of corporations, and the proof that money does not bring happiness – but most of us felt that it didn’t quite carry it off.

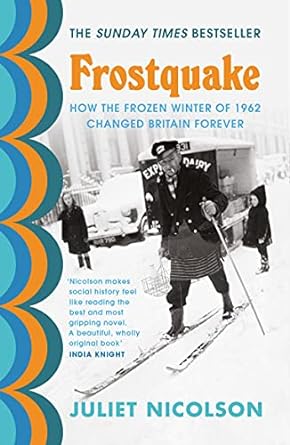

The SWFT Reading Group choice for November is Frostquake by Juliet Nicolson:

‘On Boxing Day 1962, when Juliet Nicolson was eight years old, the snow began to fall. It did not stop for ten weeks. It was one of the coldest and harshest winters for 300 years. The drifts in East Sussex reached twenty-three feet. In London, milkmen made deliveries on skis. On Dartmoor 2,000 ponies were buried in the snow, and foxes ate sheep alive. It wasn’t just the weather that was bad. The threat of nuclear war had reached its terrifying height with the recent Cuban Missile Crisis. Unemployment was on the rise, de Gaulle was blocking Britain from joining the European Economic Community, Winston Churchill, still the symbol of Great Britishness, was fading. These shadows hung over a country paralysed by frozen heating oil, burst pipes and power cuts.’

Looks like a great read as we head towards winter!

We’ll be meeting to chat about Frostquake on Thursday 23rd November, at 1pm. Please email library@swft.nhs.uk for your Teams invitation.